Quantum technologies are enabled by precise control of the state and interactions of individual quantum objects. Innsbruck physicists have now proposed a way to remotely control the state of individual quantum emitters. The underlying idea, developed by a research group led by Oriol Romero-Isart, is based on chirped light pulses. This novel approach could become a relevant asset in quantum computers and quantum simulation in the future.

In order to exploit the properties of quantum physics technologically, quantum objects and their interaction must be precisely controlled. In many cases, this is done using light. Researchers at the University of Innsbruck and the Institute of Quantum Optics and Quantum Information (IQOQI) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences have now developed a method to individually address quantum emitters using tailored light pulses. “Not only is it important to individually control and read the state of the emitters,” says Oriol Romero-Isart, “but also to do so while leaving the system as undisturbed as possible.” Together with Juan José García-Ripoll (IQOQI visiting fellow) from the Instituto de Física Fundamental in Madrid, Romero-Isart’s research group has now investigated how specifically engineered pulses can be used to focus light on a single quantum emitter.

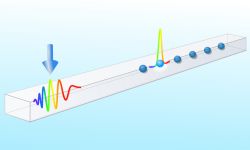

Self-compressing light pulse

“Our proposal is based on chirped light pulses,” explains Silvia Casulleras, first author of the research paper. “The frequency of these light pulses is time-dependent.” So, similar to the chirping of birds, the frequency of the signal changes over time. In structures with certain electromagnetic properties - such as waveguides - the frequencies propagate at different speeds. “If you set the initial conditions of the light pulse correctly, the pulse compresses itself at a certain distance,” explains Patrick Maurer from the Innsbruck team. “Another important part of our work was to show that the pulse enables the control of individual quantum emitters.” This approach can be used as a kind of remote control to address, for example, individual superconducting quantum bits in a waveguide or atoms near a photonic crystal.

Wide range of applications

In their work, now published in Physical Review Letters, the scientists show that this method works not only with light or electromagnetic pulses, but also with other waves such as lattice oscillations (phonons) or magnetic excitations (magnons). The research group led by the Innsbruck experimental physicist Gerhard Kirchmair, wants to implement the concept for superconducting qubits in the laboratory in close collaboration with the team of theorists.

The research was financially supported by the European Union.